Manage Files from the Command Line

Dennis Kibbe

Mesa Community College

Welcome everyone. In this module, we'll explore how to manage files using the Linux command line. It's essential for both server administration and everyday Linux use. This slide presentation was created using Reveal.js . You can access a transcript of this presentation by pressing S for speaker notes. You can access navigation help by pressing the question mark key. Audio for this presentation is artificially generated.

Module Outline

Describe Linux File System Hierarchy Concepts

Graded Quiz

Specify Files by Name

Graded Quiz

Manage Files with Command-line Tools

Guided Exercise

Make Links Between Files

Guided Exercise

Match File Names with Shell Expansions

Graded Quiz

Graded Lab

Module Summary

This outline shows our roadmap: Linux filesystem concepts, specifying files by name, file manipulation with command-line tools, creating links, pattern matching, quizzes, guided exercises, a graded lab, and the module summary.

Learning Objectives

After completing the work in this module you will be able to:

Describe how Linux organizes files and directories in a tree-like hierarchy.

Explain how absolute path and the relative path to a file differ.

Change the working directory and list the contents of directories.

Create, copy, move, and remove files and directories.

Create hard and soft (symbolic) links to files.

Use pattern matching to efficiently run commands.

By module's completion, you should be able to describe the directory hierarchy, navigate using absolute and relative paths, create, copy, move, delete files and directories, set up hard and symbolic links, and use shell expansions for efficiency.

Describe Linux File System Hierarchy Concepts

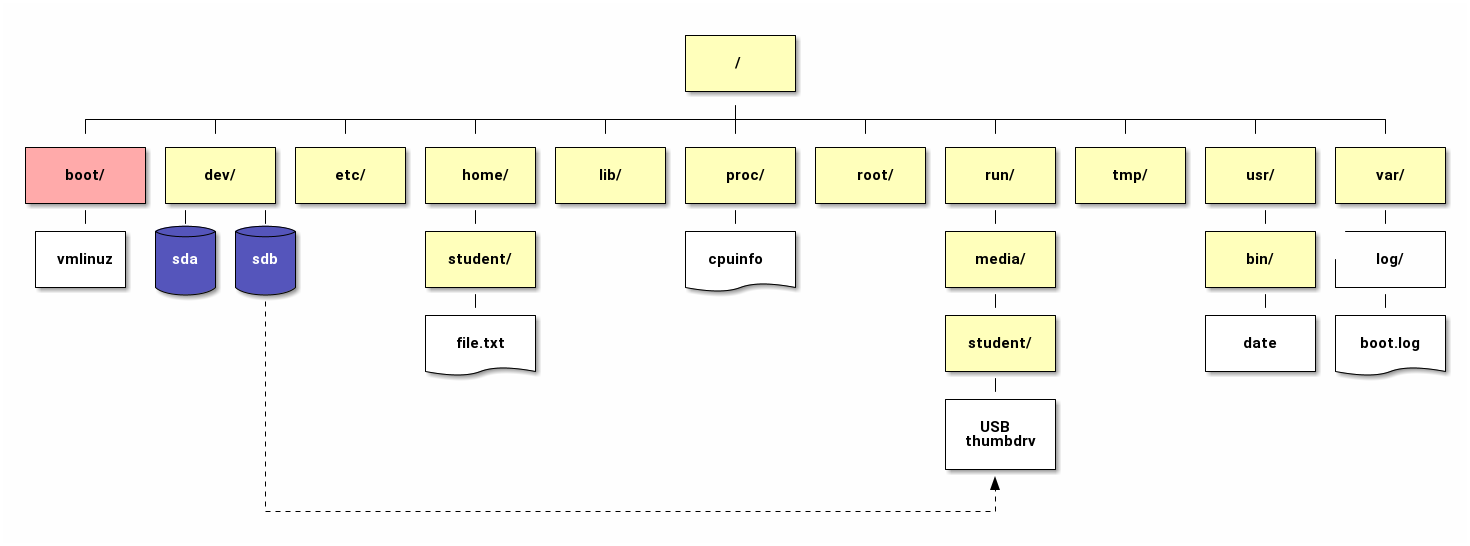

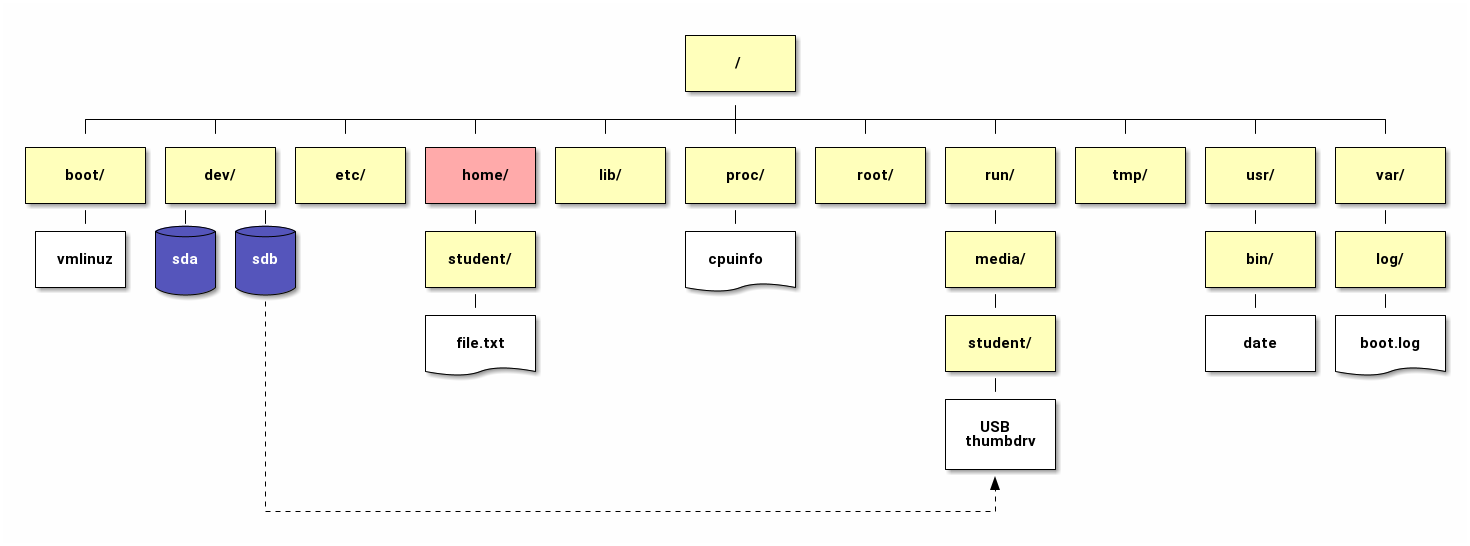

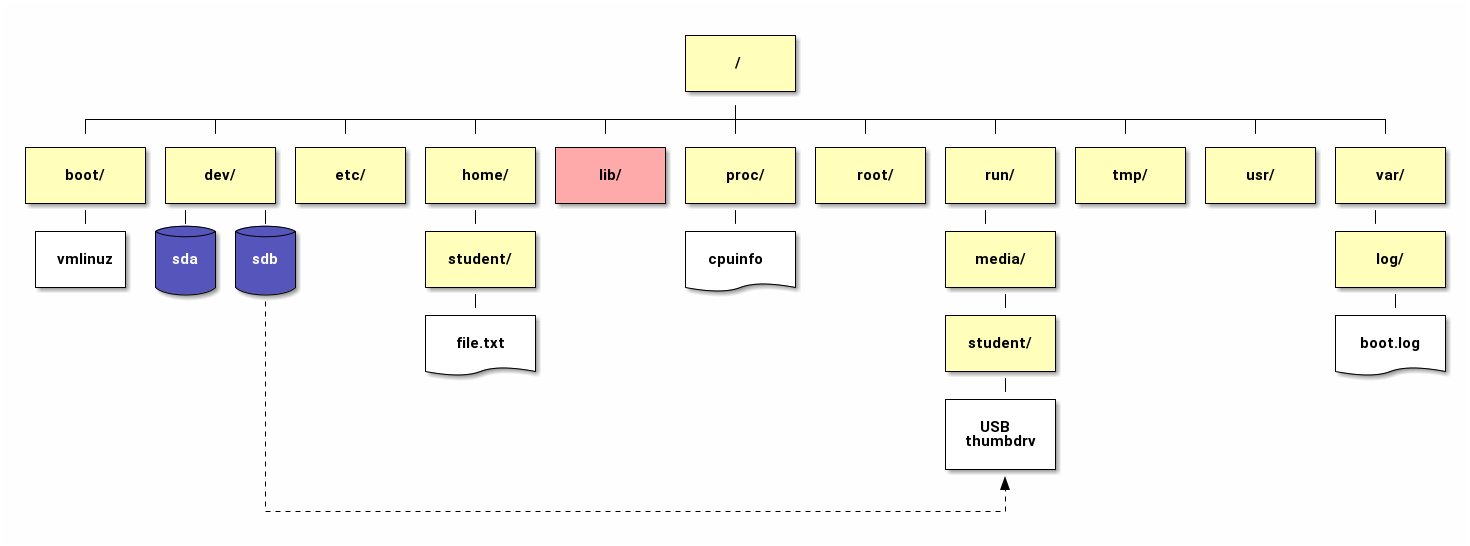

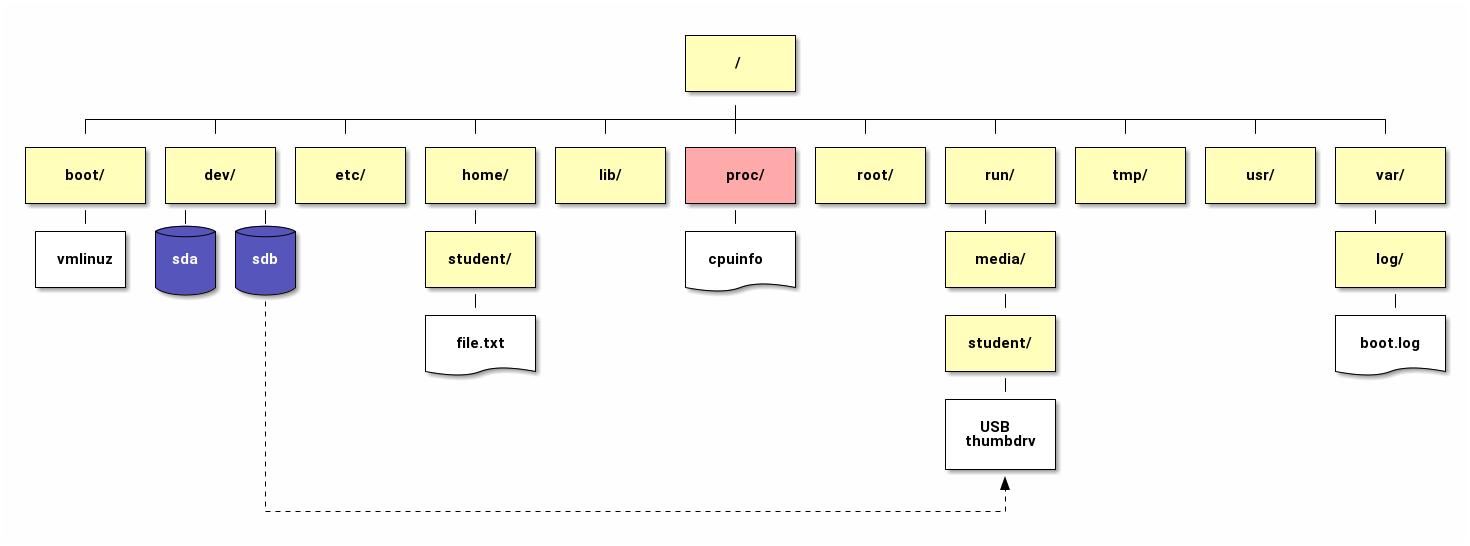

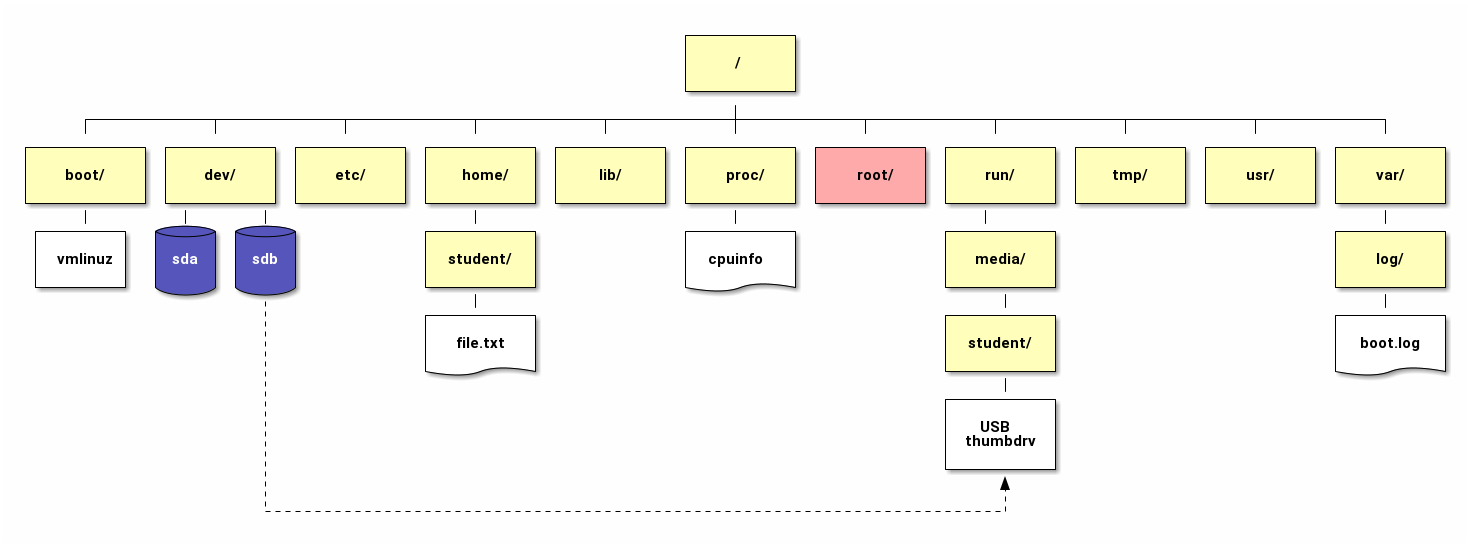

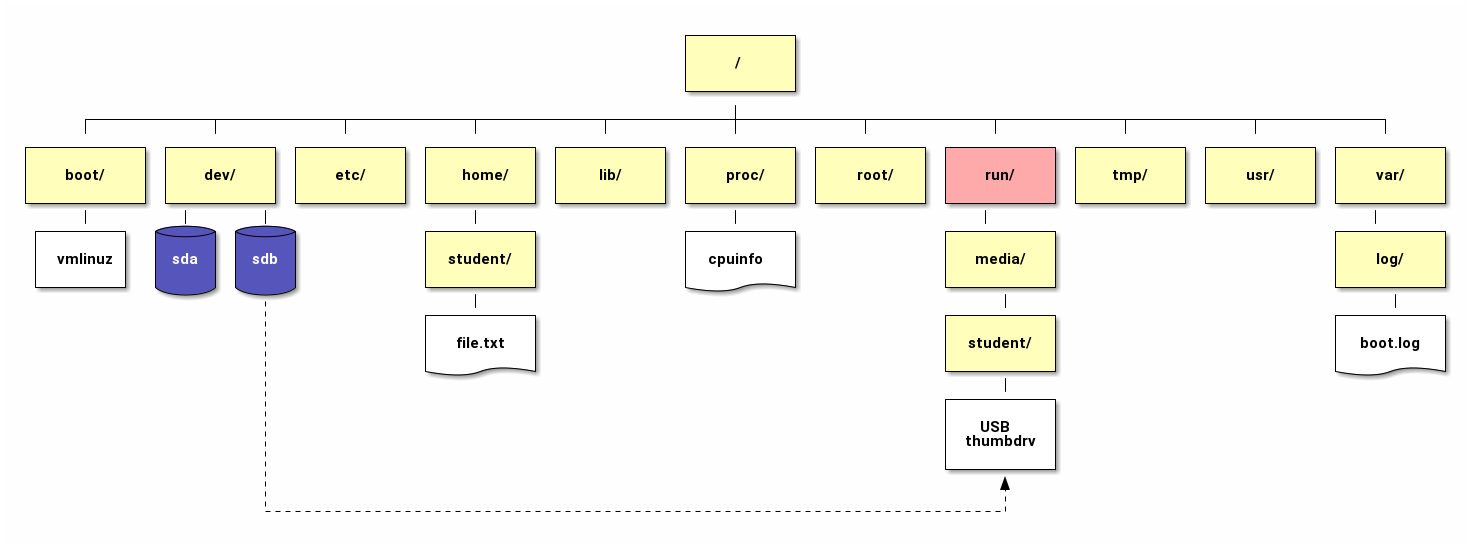

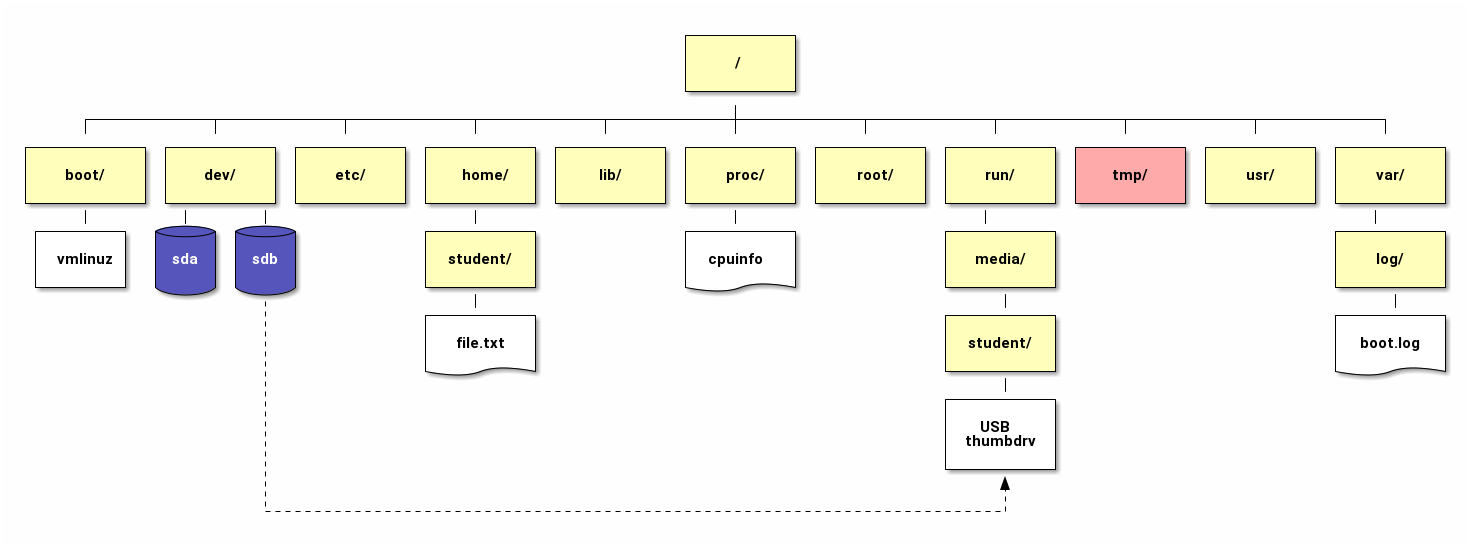

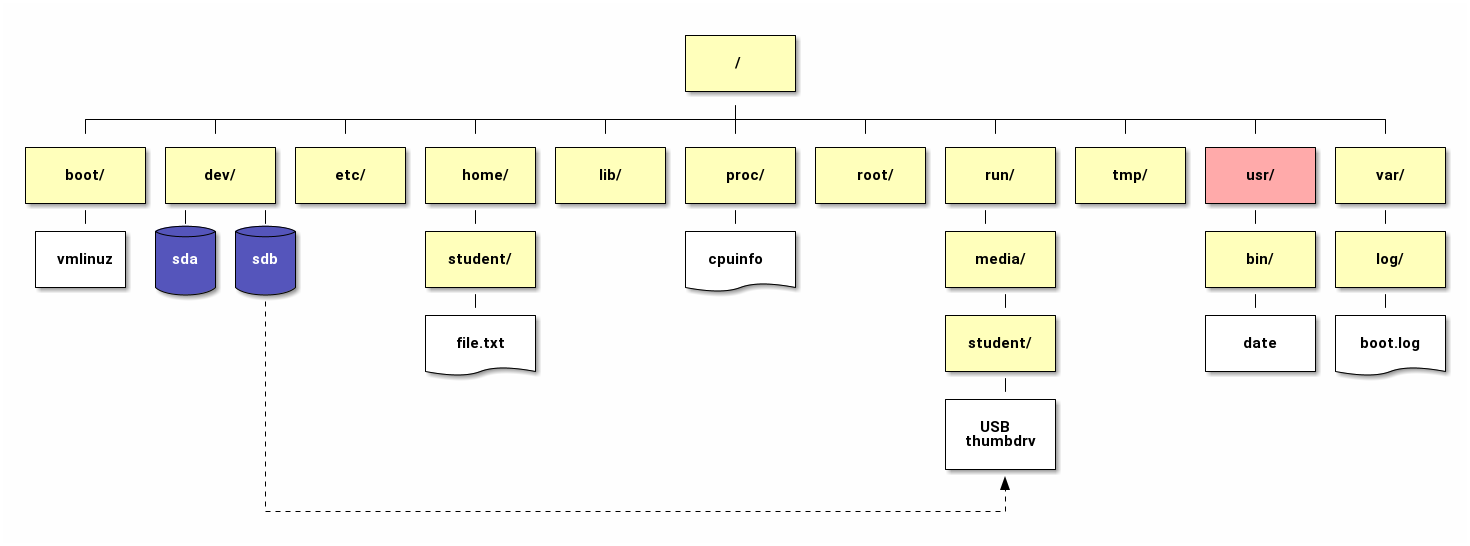

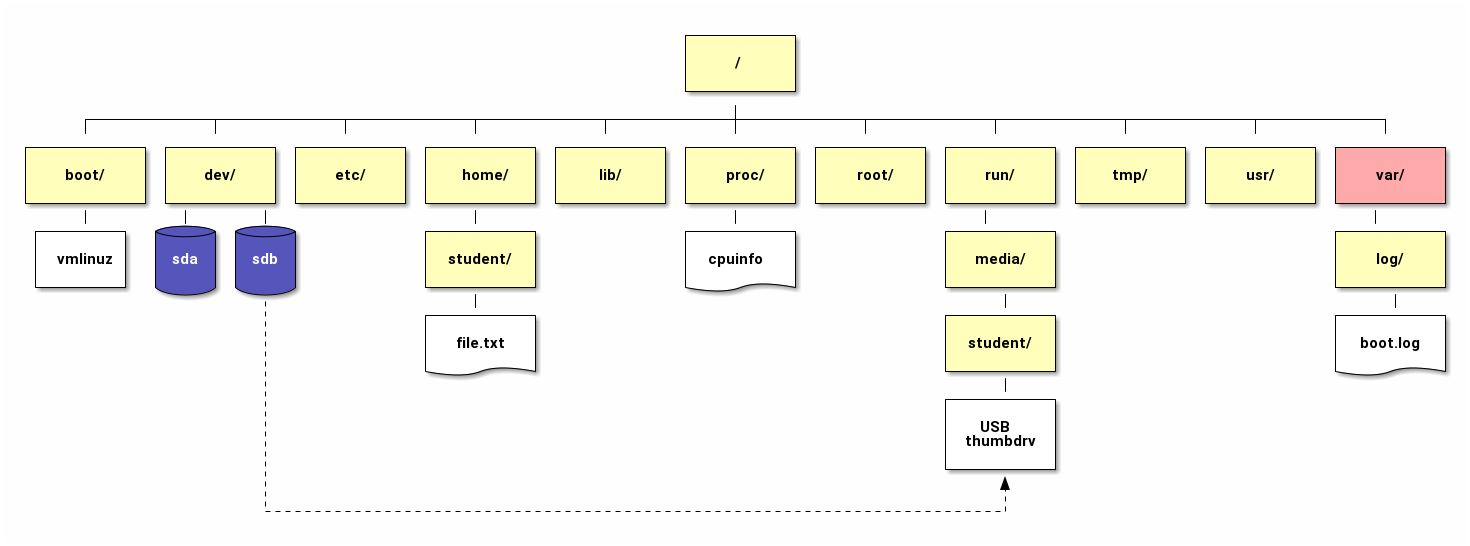

We begin with understanding the structure of the Linux filesystem—rooted in a single inverted tree, starting at a forward slash (/). This differs from Windows drive-letter systems.

The File System Hierarchy

Unlike Windows Linux organizes files into a single inverted tree-like structure even when files exist on a separate storage device. Drive letters such as C, D, and E are not used. The top of the file system is represented by a / (forward slash).

The boot Directory

The /boot directory holds files essential for booting—like the Linux kernel (vmlinuz) and initial ramdisk images, needed before mounting the root filesystem.

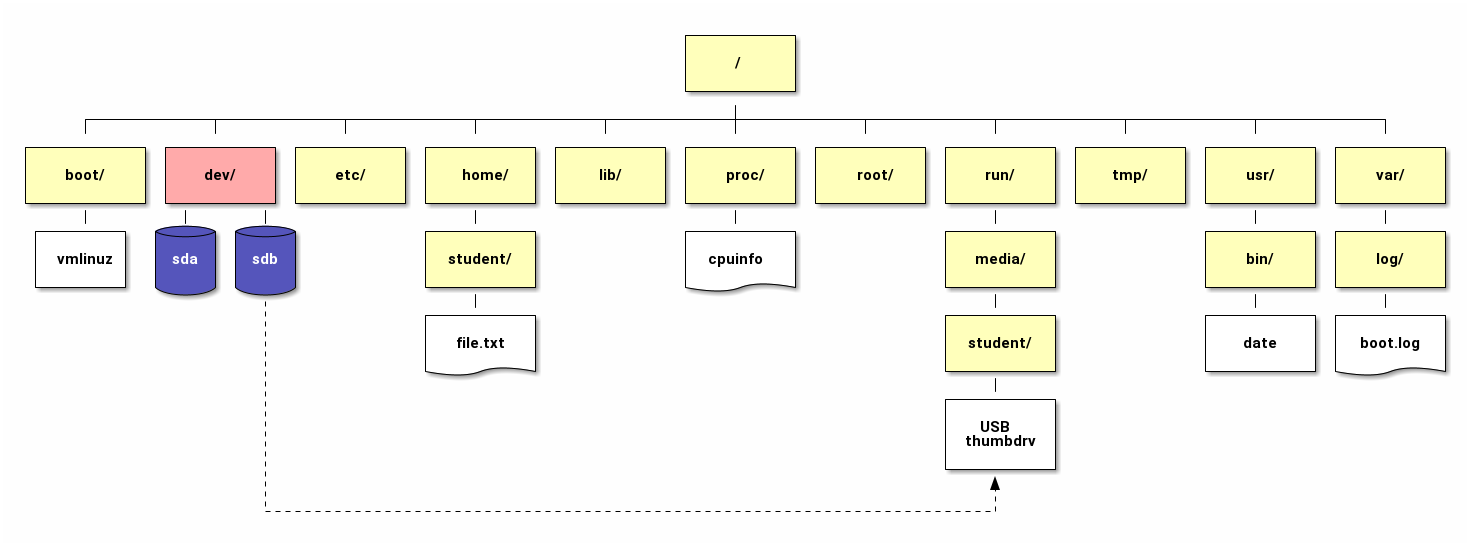

The dev Directory

The /dev directory is a virtual directory housing device files—interfaces to hardware devices. For example, /dev/sda represents a physical disk.

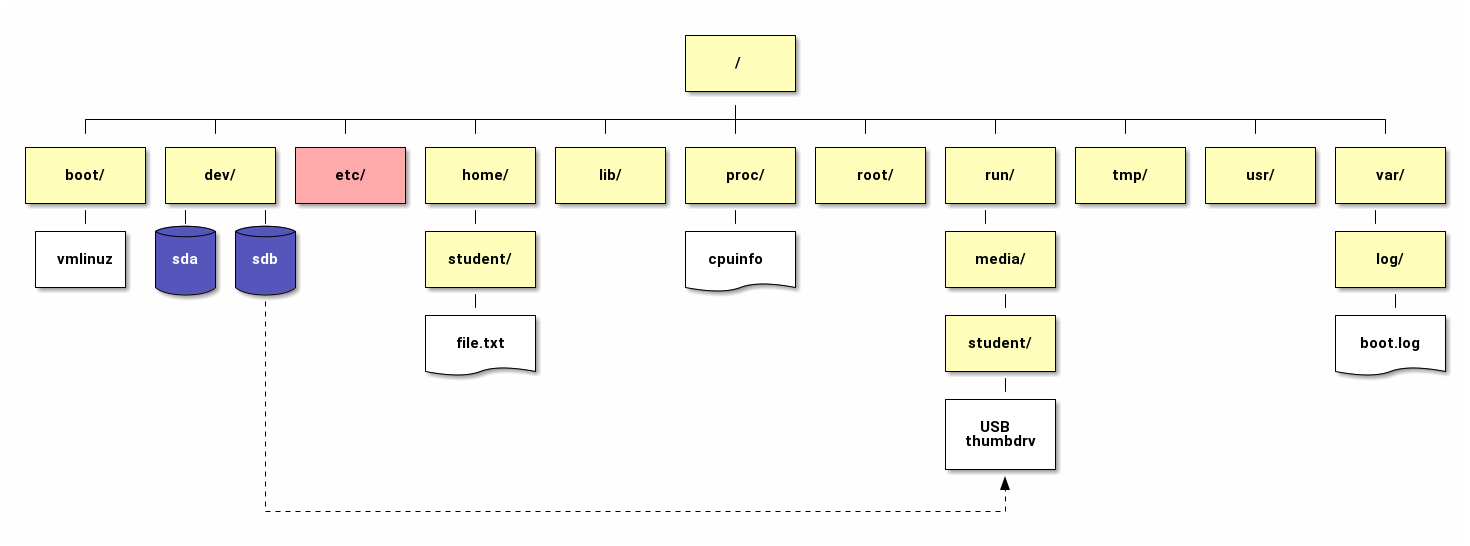

The etc Directory

TThe etc directory holds system-wide configuration files. It's where you configure services such as SSH (/etc/ssh/sshd_config) and system settings.

The home Directory

Under the home directory each unprivileged user has a personal directory. This is where personal files, configurations, and documents reside. For example, the personal files of user student are stored in /home/student.

The lib Directory

Libraries shared by programs—such as those needed for spell-checking—live in /lib or /usr/lib. These libraries support executable binaries.

The proc Directory

The proc directory is a virtual directory created when the system boots to provide information about system resources. For example, /proc/meminfo contains detailed information about system memory.

The root Directory

The root directory is the personal directory for the administrator or superuser - not to be confused with the filesystem root /. It's used when the root user logs in. However, following best practices the system administrator will work as an unprivileged user and only gain root privileges when needed.

The run Directory

The run directory is a temporary directory in memory for storing various information such as lock files and sockets.

The tmp Directory

The tmp directory stores temporary files from both users and programs. It's cleared periodically or on reboot and is writable by all users.

The usr Directory

Installed software and shared libraries are found in the usr directory. The /bin and /sbin directories are symbolically linked to /usr/bin and /usr/sbin.

The var Directory

Dynamic data—like logs, caches, mail spools—resides in /var. For example, system logs are typically found in /var/log./p>

Graded Quiz

Describe Linux File System Hierarchy Concepts

Time for a quick graded quiz: identify and describe the purpose of these key directories based on what we've just covered.

Specify Files by Name

Next, we'll learn how to access files using absolute and relative paths—crucial when navigating or executing commands.

Absolute Paths

[student@servera ~]$ ls /etc/ssh/sshd.config

[student@servera ~]$ pwd

/home/student/

The absolute path to a file always starts at the top of the file system represented by a forward slash (/) and can be used to navigate to a file from anywhere on the system. The pwd or Print Working Directory command shows the absolute path to the directory you are currently in.

The Current Working Directory and Relative Paths

[student@servera /etc/ssh/]$ sudo vim sshd.config

Using a relative path to a file requires less typing then using the absolute path. In this example, student is already in the /etc/ssh/ directory as you can see by the prompt so only the file name is needed, but that will not work from anywhere else on the system.

Navigate Paths in the File System

[student@servera ~]$ cp /etc/passwd .

Linux provides a number of shortcuts to help you navigate the system. A single period (.) represents the current directory and two periods (..) represents the parent directory. These shortcuts can be used in commands. In this example a file is copied to the current directory from the /etc directory. Note the single period as the destination. A single period represents the current working directory in this case student's home directory.

Move a File to the Parent Directory

[student@servera Documents]$ mv file.txt ../

[student@servera Documents]$ ls ../

Documents Music Desktop Pictures Videos file.txt

Using mv file.txt ../, we move the file into the parent directory. You can then verify it exists there with ls ../.

Graded Quiz

Specify Files by Name

Manage Files with Command-line Tools

Create, copy, move, and remove files and directories

Creating, copying, moving, and removing files are common operations. In this section you will learn command line tools to perform these tasks.

Create Empty Files

[student@servera ~]$ touch file file1 file2 file3

[student@servera ~]$ ls file*

file file1 file2 file3

The touch command is useful for creating one or more empty files when you need files to test a command. If used with files that already exist touch will update the timestamp on the files. This can be useful if you want all the files to have the same modification date when distributing them in an archive.

Create Directories

[student@servera ~]$ mkdir -v 'My Stuff'

mkdir: created directory 'My Stuff'

The mkdir command creates one or more new directories. If the directory name contains a space the name must be enclosed in quotes. The -v option confirms that the MyStuff directory was created.

Copy Files and Directories

[student@servera ~]$ cp file1 file2

The cp command copies an existing file to a new file. If the new file name already exists it is overwritten without warning. The source file is always the first argument to the command followed by the destination file name. If the last argument is a directory the file or files are copied into that directory.

Move Files and Directories

[student@servera ~]$ mv file1 Documents/file3

[student@servera ~]$ ls Documents/

file3

The mv command serves two purposes. It can move a file to a new location or rename a file. Here file1 is moved from student's home directory to the Documents directory and renamed to file3.

Move and Rename Files and Directories

[student@servera ~]$ mv file1 file2 Documents/

[student@servera ~]$ ls Documents/

file1 file2

This command takes two files—file1 and file2 —and moves them into the Documents directory. In Linux, the mv command means "move." It removes the file from its original location and places it in the new destination.

If the destination directory exists, Linux interprets the command as "move the listed files into this directory." If the destination does not exist, Linux may interpret the last argument as a new filename. That means you could unintentionally rename a file instead of moving it, so always confirm the directory exists before running the command.

After moving the files, the ls Documents/ command lists the contents of the Documents directory, confirming that file1 and file2 are now there.

Remember, mv can also be used to rename files. For example, mv oldname newname changes a file's name.

The key idea here is that mv handles both moving and renaming. Context determines which operation occurs. Always double-check your destination to avoid overwriting or misplacing files.

Remove a Directory

[student@servera ~]$ rmdir MyStuff

rmdir: failed to remove 'MyStuff': Directory not empty

In this example, we are working with the rmdir command, which stands for "remove directory".

Linux responds with an error message because rmdir can only remove empty directories. If the directory contains files or subdirectories including hidden files, the command cannot complete the request.

This behavior is intentional — it prevents accidental loss of data. Before removing a directory, Linux wants to be sure you are not deleting anything important.

To successfully remove the directory, you would first need to delete or move the contents inside it. Once the directory is empty, rmdir will work without errors.

Remove a Directory Containing Files

[student@servera ~]$ rm -rf MyStuff

In this command example, we are using rm -rf to remove a directory that contains files:

Let’s break down what this command does:

rm means remove .-r stands for recursive — it allows the command to go inside the directory and remove everything it contains, including subdirectories and files.-f stands for force — it instructs Linux to remove items without asking for confirmation, even if they are write-protected.

This combination makes rm -rf very powerful, but also potentially dangerous. With this command, there is no built-in undo. If you accidentally target the wrong directory, the system will erase everything inside it immediately.

That is why it's important to:

Double-check the directory name before pressing Enter,

Avoid running this as the root user unless necessary,

Use safer alternatives when possible, such as rm -r without -f, which prompts before removal.

This command is common in system administration, but always treat it with caution — especially in production environments.

Guided Exercise

Manage Files with Command-line Tools

Let's walk through an exercise. Step‑by‑step we'll create files, move them around, and verify using the tree utility. Check Canvas for helpful Lab Notes.

Make Links Between Files

Create Hard Links Between Files

[student@servera ~]$ ln file1 file2

[student@servera ~]$ ls -li file1 file2

1643415 -rw-r--r-- 2 user user 0 Jun 29 06:43 file1

1643415 -rw-r--r-- 2 user user 0 Jun 29 06:43 file2

A hard link points directly to the data on the file system not to a file name. A file name is just a reference to where the data is stored on the file system. You can create multiple hard links to the data. As long as one link still exists the data is accessible. Only when the last link is removed is the data no longer accessible. In this example a hard link is created from file1 to file2. The ls -li command shows that each file has two links and the inode numbers for each file are the same. An inode tells the system where the data is on the storage device.

Limitations of Hard Links

Hard links can't cross filesystem boundaries, nor be created to directories to avoid recursive loops.

Create Symbolic Links

[student@servera ~]$ ln -s soft_link file1

[student@servera ~]$ ls -l soft_link

l rwxrwxrwx 1 student student 8 Jun 29 soft_link -> file1

A symbolic or "soft" link points to a file name not to an inode. If the referenced file is deleted the link is broken and the data is lost. In this example a soft link named soft_link is created to file1. The ls -l command shows that soft_link is a link. If file1 is deleted the link is broken and the data is lost.

Guided Exercise

Make Links Between Files

In this Guided Exercise, you'll create both types of links using relative paths and tab completion for efficiency.

Match File Names with Shell Expansions

Using shell expansions, you can match patterns and process multiple files quickly.

Command-line Expansions

Work lazy; work smart

[student@workstation ~]$ ls Pictures/*.jpg | wc -l

46

[student@workstation ~]$

When you type a command at the Bash shell prompt, the shell processes that command line through multiple expansions before running it. You can use these shell expansions to perform complex tasks that would otherwise be difficult or impossible.

Pathname Expansion and Pattern Matching

Pattern

Matches

*

Zero or more characters

?

A single character

*

Zero or more characters

[[abc]]

Any one character in the enclosed class

[[!abc]]

Any one character not in the enclosed class

[[:alpha:]]

Any alphabetic character

[[:alnum:]]

Any alphabetic character or digit

[[:digit:]]

Any single digit from 0 to 9

Pathname expansion expands a pattern of special characters that represent wild cards or classes of characters into a list of file names that match the pattern. See table in textbook.

Brace Expansion

[student@servera ~]$ touch file{1..5}

[student@servera ~]$ ls file*

file1 file2 file3 file4 file5

Tilde Expansion

[student@servera Documents/MyStuff]$ ls ~/Videos

video1.mp4 video2.mp4 video3.mp4